From Africa to Latin America to Asia, babies have been carried in cloth wraps on their mothers’ backs for centuries. Now, the practice of generations of women could become a lifesaving tool in the fight against malaria.

Researchers in Uganda have found that treating wraps with the insect repellent permethrin cut rates of malaria in the infants carried in them by two-thirds.

Malaria kills more than 600,000 people a year, most of whom are children in Africa under five years old.

The trial involved 400 mothers and babies aged about six months old, in Kasese, a rural, mountainous part of western Uganda. Half were given wraps, known locally as lesus, treated with permethrin and half used standard, untreated wraps that had been dipped in water as a “sham” repellent.

Researchers followed them for six months to see which babies developed malaria, re-treating the wraps once a month.

Babies carried in the treated wraps were two-thirds less likely to develop malaria. In that group there were 0.73 cases per 100 babies each week, and in the other there were 2.14.

One mother who attended a community session on the trial results stood up to tell the gathering: “I’ve had five children. This is the first one that I’ve carried in a treated wrap, and it’s the first time I’ve had a child who has not had malaria.”

The results had everybody “tremendously excited”, said co-lead investigator Edgar Mugema Mulogo, a professor of public health at Mbarara University of Science and Technology in Uganda.

“We suspected that there would be potential benefit – what was quite outstanding was the magnitude.”

His co-lead investigator Dr Ross Boyce, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was so astounded he said they should rerun the results to double-check them. “I wasn’t sure it was going to work, to be honest with you,” said Boyce. “But that’s why we do studies.”

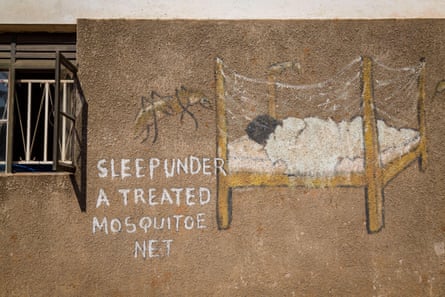

The mosquitoes that carry malaria parasites generally feed at night, which is why bed nets have historically been so key in fighting the disease.

However, they are increasingly biting outside that time frame, in the evening or early morning, in what could be an adaptation to mosquito nets.

Mulogo said: “Before you go to bed, when you’re outdoors – particularly in the rural community, where the kitchens are outside, probably they have the evening meal outside – we also need to find a solution ensuring that we can prevent those bites likely to transmit malaria.”

Wraps are everywhere in those communities, he said, used not only for carrying infants but also as shawls, bed sheets and aprons. He would like to see treated wraps become part of the suite of tools used to tackle malaria in Uganda. Already there is demand in the communities that took part in the study, he said.

Health officials in Uganda and international malaria leaders at the World Health Organization have expressed interest in the research. It could help babies, as protection passed on through the mother’s antibodies wanes, often before they can be vaccinated.

It builds too on earlier research treating shawls in Afghan refugee camps that found a similar levels of success. WHO guidelines already recognise the role permethrin-treated clothing can play as individual protection against malaria.

Mulogo is hopeful there could one day be local production of impregnated wraps. “It presents a very good business opportunity for local industry.”

There are a series of steps that will need to be taken before any rollout, the researchers said, including evidence that the intervention works in other settings.

Boyce said the insecticide has a good safety profile, and has been applied to textiles for years – including by the US military, where he first came across the idea when serving in Iraq.

Babies carried in permethrin-treated wraps were slightly more likely to develop rashes, at 8.5% v 6%, although none were sufficiently troublesome that they withdrew from the study. Boyce and Mulogo say further research will be needed to confirm the safety of the intervention, although any risks are likely to be outweighed by the benefits.

Boyce would like to see whether treating school uniforms can also cut malaria rates. But he said there was no money for the next research stages “in the bank accounts quite yet”.

He is hopeful that the simplicity of the intervention will appeal to funders. “My mother can understand what we did. It’s not some specific inhibitor of a fusion protein or something like that. We took some cloth and we soaked it. And it’s dirt cheap,” he said.

Leave a Reply